It’s almost impossible to review Look Who’s Back without talking about the state of contemporary society and the role of the media plays in informing our opinions. For that reason alone it’s worth reading.

It’s almost impossible to review Look Who’s Back without talking about the state of contemporary society and the role of the media plays in informing our opinions. For that reason alone it’s worth reading.

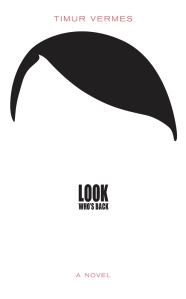

A book in which Hitler materialises in modern day Germany is bound to draw attention. One in which he gains not only acceptance but also garners respect and admiration is sure to be controversial, but is it worth the fuss?

On balance, yes. But only just. Humour is subjective. I have a fairly liberal attitude to comedy and when it comes to laughter, I think most things are up for grabs. If you can make emotive subjects funny that’s a talent. If you can’t, and you piss a lot of people off, then you’ve misjudged your audience. Whether you’re branded ‘sick’ or’edgy’ merely depends on a complicated formula based on the number of people who have heard of you and what newspaper they read. Timur Vermes is obviously charting choppy waters with this book, but I think anybody offended by this book probably hasn’t read it, or at least failed to look for anything other than what they expected to find.

Having said that, the book would be funny whoever it was that had travelled in time. Anybody plucked from WWII and thrust into the 21st century is going to find the place absurd. We all carry computers around in our pockets that are capable of accessing the sum total of the world’s knowledge. We can communicate with almost anybody anywhere on the planet, and what do we do? We send them pictures of cats. Given that Hitler stood at the head of a massive propaganda machine, having him flicking from channel to channel of daytime TV does have a certain appeal, but replace him with any temporally dislocated person from the 1940s and the effect would be much the same.

Where this book becomes uncomfortable, is in its examination of the ‘never again’ aspects of the Third Reich. We all like to imagine we would never have taken part in Hitler’s regime, but Vermes gently suggests we’re all one forceful personality from committing the unthinkable. Gentle though it is, I think his assertion is a little off the mark. Hitler is treated as a comedy act. The other characters in the book find it impossible to see him as anything other than a comical curiosity. This is human nature; how could one do anything else? Nobody could seriously pretend to be Hitler in 2014. So it is that Hitler is feted by media types as a bold comic, fearlessly crossing boundaries. Yet there seems to be very little intelligent dissent about this mysterious ‘comic’. Considering the shit-storm kicked up by the idea that Jonathan Ross might present some awards, enough to make the national press, it’s hard not to imagine Twitter spontaneously combusting and television studios being picketed. Yet none of this seems to happen.

So whilst Hitler’s forceful personality wins over the people he meets, I’m not sure it necessarily means the world would goose-step in his wake. To be fair Vermes, doesn’t suggest this will be the case, but he does imply lots of people might think about it. Hitler as painted by Vermes (Dictator with the Pearl Earing?) is a pin up for UKIP voters. It would be an interesting exercise to take quotes from the book out of context to see what UKIP members make of them. You could sell tickets to watch them beat a hasty retreat when you reveal where the observations came from.

This is where Vermes has been clever. The views Hitler expresses, or rather the way in which they are expressed, one has to grudgingly admit do make some sense, and therein lies the novel’s power. Even monsters can be appealing. Yet I feel this is disingenuous. Extreme views of any stripe can find credence somewhere. Vermes contention is that even people with moderate views (or perhaps no views of their own) could fall under Hitler’s spell. To an extent this is irrefutable but in reality the character here is not Hitler, he’s a fictional character created to make a point. The circumstances under which Hitler rose to power are very different to those we find today, and I’m not sure the amused tolerance Vermes’s Hitler enjoys is a realistic picture.

Part of this time-travelling dictator’s acceptance comes from misunderstandings. I think it’s that true that it is human nature to see best intentions and to ignore the improbable, if a more palatable explanation is offered, but all too often Vermes relies on his characters talking at cross purposes. One of the most quoted passages of the book is,

“There’s just one thing I want to get straight,” Frau Bellini said, suddenly looking at me very seriously.

“What is that?”

“We’re all agreed that the Jews are no laughing matter.”

“You are absolutely right,” I concurred, almost relieved. At last here was someone who knew what she was talking about.

On it’s own this is funny, but it is the first and best example of Hitler’s double meanings. I guess there might be something here to be said about the duality of language; we hear what we want to hear, but the repeated use of this device means that by the end of the novel it starts to feel like a very long episode of Neighbours.

So, all this is a very long-winded way of saying I have mixed views about Look Who’s Back. It’s a fascinating, thought-provoking idea, that gives rise to some laugh out loud moments. It’s an acerbic take on modern society, but the overall concept is stretched a little thin by the end. I imagine a lot of people will read this book, but in a couple of years time I suspect it will be little more than a literary curiosity. Finally, if you enjoyed this book or are wavering about reading it, let me point you in the direction of a similar and in my opinion superior novel Hope: A Tragedy by Shalom Auslander. It’s not really same, but it is dark, satirical and more subtle than Look Who’s Back.

Many Thanks to Corinna at MacLehose Books for sending me a copy of this book.